Victorian Kitchen Garden Glasshouse Reinstated

Historic Victorian Kitchen Garden Glasshouse Reinstated at Benthall Hall, Shropshire

Autumn was beginning to cast its burnished light on the fruit trees in the orchard of the walled kitchen garden at Benthall Hall (pronounced as “gentle”) as a varied group of gardeners and historians gathered in the unremarkable north-east corner to discuss the very vague possibility of reinstating a glasshouse that had previously occupied this spot. The only remaining evidence of which was a long run of unusually wide and rather dilapidated cold frames. Nothing noteworthy, you might say, about finding cold frames in a setting such as this but their intriguing design hinted at something less-than-usual going on in this walled garden over the preceding years and, indeed, that proved to be the case.

The remains of the 1900’s glasshouse before the reinstatement work began

Amongst those present was Benthall’s Gardener in Charge, Nick Swankie, who had a vision. A vision he’d been quietly nurturing for many years but one which, now, finally, felt like it had the air of possibility about it. And having spent more than 2 decades gardening the Benthall land, first directly for the family and then, more recently employed by the National Trust, no one knows more about the horticultural legacy lying dormant in these abandoned base walls than he does.

Benthall Hall

A brief history

Benthall Hall was built for the Benthall family in the late 16th century, and it’s gabled and pentagonal-bayed ashlar walls, draped in wisteria in early spring, have a welcoming, unimposing air. A hotch-potch of angles and protrusions that seem to have grown out of the landscape over time, rather than being the result of human intervention. And this light touch permeates every inch of the surrounding land and gardens too. The property was bequeathed to the National Trust in 1958 and many of their team of volunteers have connections with the Hall and the Benthall family that go back generations. Their welcoming enthusiasm and intimate knowledge of the place and the people that lived here is infectious and, with less footfall than neighbouring Trust properties, it’s quite possible to imagine yourself living here.

Left, Gardener-in-Charge Nick Swankie contemplates the achievement as we near completing the greenhouse. Centre and right, the new greenhouse was celebrated with an opening party with fundraisers and contributors all invited. No one is ever too far away from a cake at Benthall. Our team were so well looked after, they now expect cake wherever they go!

George Maw

Despite being built for, and occasionally still inhabited by the Benthall family, there have been a number of other occupants over the centuries who have left a considerable imprint on the place, however. Let’s start with George Maw who, along with his brother Arthur was the first to have documented the history of the walled garden. The brothers had relocated their tile manufacturing business to the area to take advantage of the high-quality clay and coal available – the same rich seams that neighbouring Iron Bridge was built on. The Benthall Works at Brosely grew to be the largest tile manufactory in the world, at the time, producing over 20 million tiles a year and whose list of clients included the Royal Family, Alexander II of Russia, two maharajas, nine dukes, twelve earls, the railway companies, thirteen cathedrals, thirty-six hospitals, fifty-three public buildings, nineteen schools and colleges, and five warships! (1) They stamped their ubiquitous identity on Victorian progression the world over.

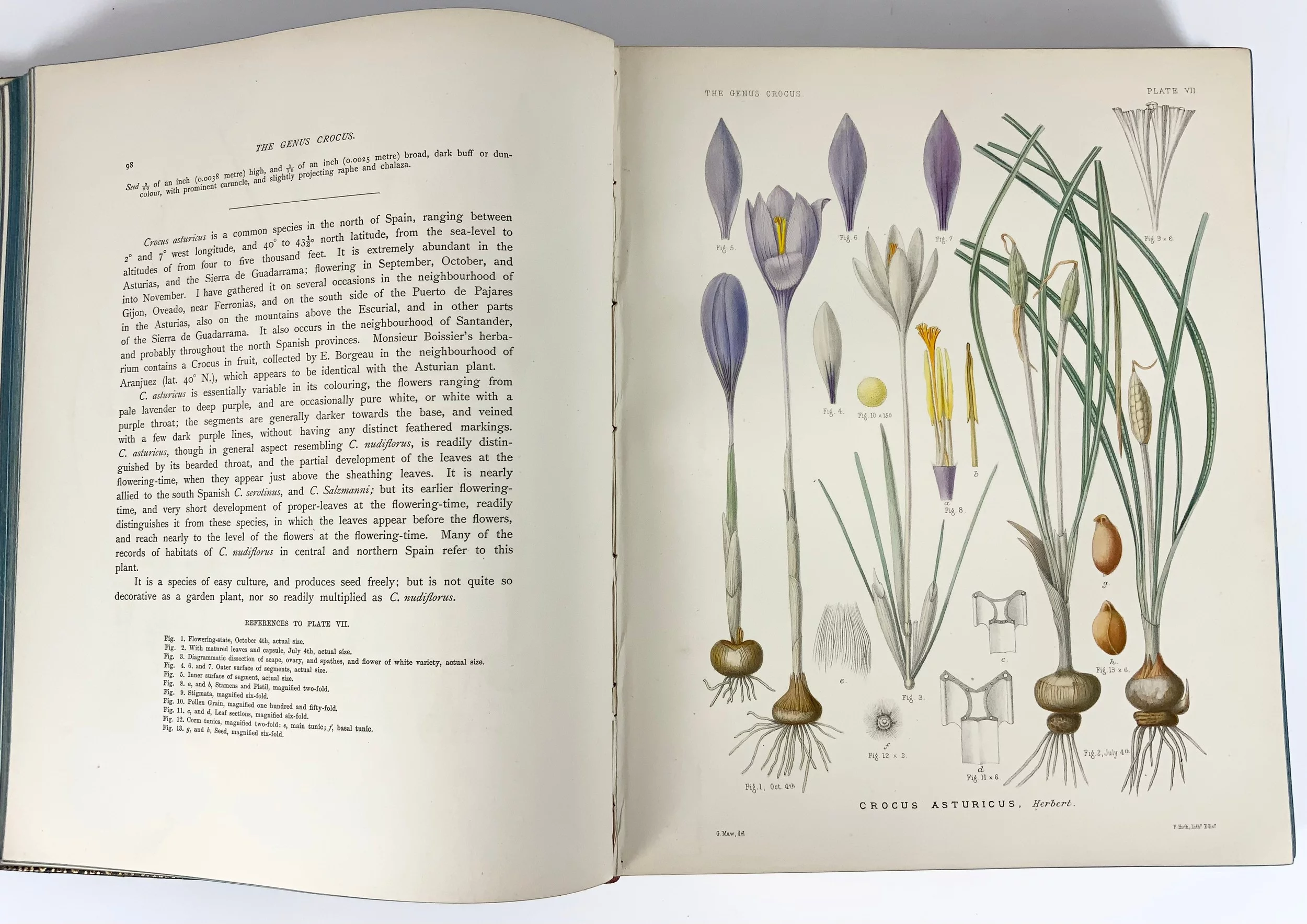

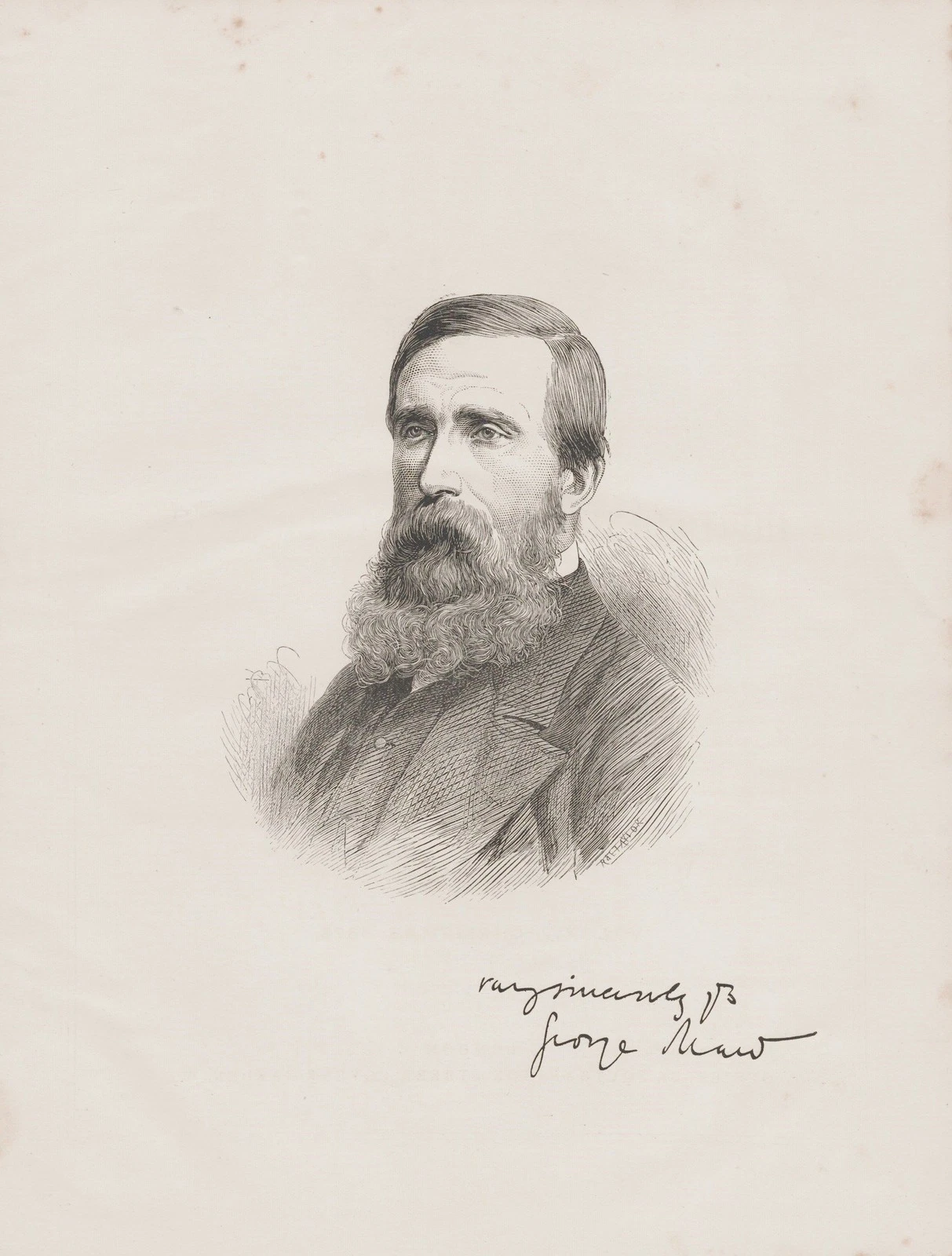

Alongside his hugely successful business, George was a well-respected botanist and artist with a passion for collecting plants from around the world and a particular interest in crocus. In 1886 he published ‘a Monograph of the Genus Crocus’, collating over 10 years of collecting and researching a total 67 species, many of which he brought to Benthall, and illustrated with his own drawings – a volume of work still referenced to this day.

Left and centre, The Genus Crocus is still referenced today. Right, George Maw

Maw was friends with many of the notable horticultural thought-leaders of the time, too, including the director of Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, and the evolution theorist Charles Darwin, who used his expertise in plant collecting to aid his research in 1869.

These relationships brought many notable plantsmen to Benthall to see the trials he was conducting with the plants he had collected. It was noted that even in November, plants from Europe, Asia minor and north Africa were flourishing thanks to the glasshouses in which they were able to maintain the right climate.

Among those was the trailblazing gardener and author William Robinson (1838 – 1935), whose publications included the groundbreaking “The Wild Garden” and whose concepts, which continue to inspire and inform, are manifested at the gardens of Gravetye Manor. Robinson was a great friend of George Maw’s, spent a lot of time at Benthall and was hugely influenced by Maw’s naturalistic approach.

Left: William Robinson © The William Robinson Gravetye Charity. Right, Gravetye Manor. © Great British Gardens

In the 1881 Gardeners Chronicle, Robinson wrote of Benthall:

“let no one think this is a mere botanical garden, with its formal rows of weeds diversified here and there by some plant of more attractive guise; let him think of it rather as a collection of the choicest, rarest, and most intrinsically interesting plants, selected with quite unusual care and knowledge, arranged with rare judgement and taste, and cultivated with no common skill.”

Swankie allows this philosophy to permeate the grounds at Benthall to this day, adopting and adapting this quote to serve as a manifesto for his own contribution to the tale. Everything he and his team of volunteers do must meet the standard:

“Nicest, choicest, bestest (but not necessarily the rarest)”

Left, the Wilderness stays true to Maw’s theories on naturalistic planting. Right, Nick’s No-Mow May practice would have been approved of by Maw. Every year he chooses a pattern to mow from June. This year it’s in celebration of the new greenhouse.

There must have been some interesting conversations between these two horticultural pioneers, with Maw & Co’s tile manufactory being at the epicentre of the industrial revolution and, no doubt, funding Maw’s ability to indulge in his passions of foreign travel, plant collecting, writing and drawing. Whilst Robinson was known to be hugely influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement which, to a certain degree, stood against mass production, or at least against “the manufacture of an object being broken into small, separate tasks, meaning individuals had a very weak relationship with the results of their labour” (3).

The Arts & Crafts Movement

This principle of the Arts and Crafts movement is a thread which runs through our business to this day, with each of our greenhouses made individually by a small, highly skilled team who handle every step of the process from design, machining and frame assembly right through to the installation in your garden. This is not mass production!

“The greenhouse looks like it’s always been here” An observation repeated by many of Benthall’s volunteers at the opening party.

William Robinson became a highly influential character, popularising the use of now-commonly used gardening devices such as secateurs and the hose pipe, alongside design ideas which included the planting of alpines in rock gardens and his mixing of native and exotic plants in a “herbaceous border” to give year-round texture, colour and interest. Benthall has a significant rock garden flanking the house which will undergo a full restoration as part of work being done in recognition of the 140-year anniversary of the publication of ‘A Monograph of the Genus Crocus’, and alpines are as integral a part of Benthall’s horticultural legacy as crocus.

Who inspired who? A bit of both, no doubt.

In 1871, Robinson’s launch of a popular weekly gardening journal called “The Garden” (eventually known as Gardens Illustrated) gave him a platform from which to talk about his ideas which also included his theories on the importance of green space for health and wellbeing alongside ahead-of-their-time theories on sustainability and biodiversity (4). So much of what Robinson stood for resonates with our personal and business values.

The Batemans & Biddulph

Maw’s tenure at Benthall spanned from 1853 to 1886 and then in 1890, Robert Bateman, third son of James Bateman, the distinguished horticulturalist, landscape designer and creator of Biddulph Grange, moved in with his wife Caroline Octavia Howard.

Robert and Caroline Bateman, © Victorianweb.org

The couple moved to Benthall from nearby Biddulph Old Hall where they had been living since 1883, when they married. Robert had already created a garden there, described locally as a “very paradise of woodland scenery…” (5) and with garden design in his blood, it was inevitable that he would leave his own imprint on Benthall’s gardens. His legacy includes the Fairy or Pixie Garden, now known as the Rose Garden, along with its two-storey Elizabethan style dovecote – officially Robert’s studio or reading room but should be thought of more accurately as a Victorian “man-cave”, Nick confides in us.

Left, Bateman’s Dovecote in what is now called the Rose Garden. Right, a view of the Walled Kitchen Garden

Reimagining the Past

Sadly, there is no evidence left of the glasshouses Maw was using for his trials in the mid to late 1800’s. In fact, it’s not until between 1902 and 1927 that a glasshouse is clearly shown in records. Since Bateman continued his tenancy until 1906, it’s vaguely possible that he was responsible for the installation of this greenhouse – a mono-pitch lean-to situated in the northeast corner of the walled kitchen garden and, without the garden’s prior connection to George Maw, one would assume a typical addition to a walled garden of this period with its main purpose being productive rather than experimental. But it is thought that this greenhouse was a continuation of the legacy left by Maw in the cultivation of unusual and tender species.

“The Glasshouse formed a key element to the cultivation of the walled gardens allowing species of plant that are susceptible to cold and wet climates to thrive. Though the glasshouse in the walled garden was not the one used by George Maw, it was a continuation of the processes Maw had developed during his Benthall Hall Tenure.” National Trust Heritage Impact Statement, 2024

By 1964, however, this too disappears from maps, and by 2004 only the footprint of this greenhouse remains. When we arrive on site in late 2022 to begin discussing the project, there’s a sense something is missing from this corner of the garden. Reinstatement is necessary to complete this working part of the garden and should be an integral asset to the Benthall gardening team.

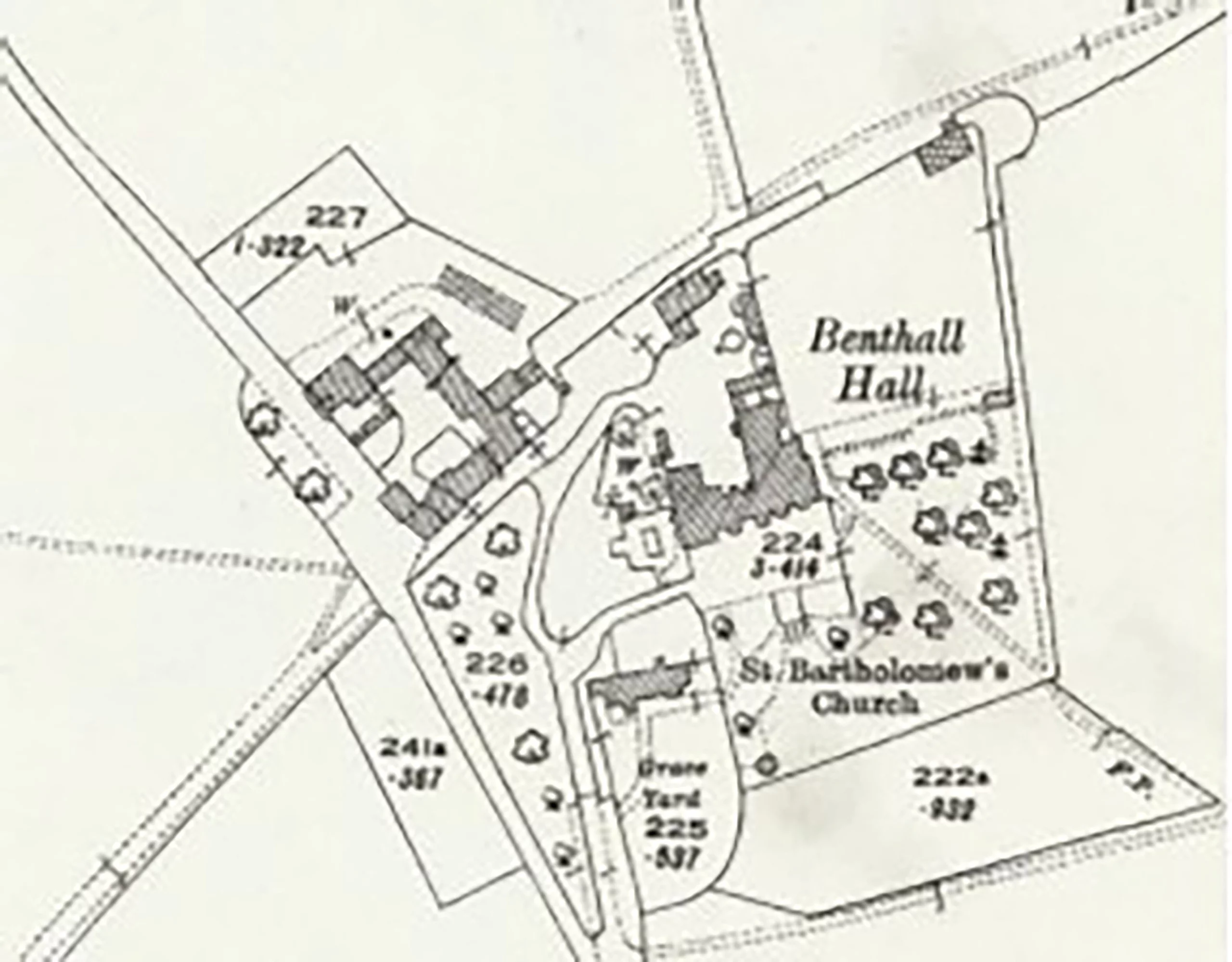

Left, map of Benthall Hall 1881 showing no greenhouse. Right, map from 1927 showing the greenhouse in the top right hand corner. Source: National Library of Scotland/NT Statement of Significance

“It will bring the immediate area out of disrepair and open up the space for visitor interpretation”. National Trust Heritage Impact Statement, 2024.

On a “behind the scenes” tour Nick gives me during the installation phase of the new greenhouse; he indicates another rather overgrown area sandwiched in between the hall and the walled kitchen garden. Apparently, evidence has been found there of previous glasshouses and it’s safe to assume that Maw would have had more than one. It’s such a shame there is no pictorial evidence of their design, but, whilst there is nothing left of the structure of the early 1900’s glasshouse we are replacing either, their evidenced existence coincides with a golden era for glasshouses and growing under glass.

Left, evidence of past glasshouses has been found here. Right, the original cast vent opening gear salvaged and restored in the Tomato House at nearby Attingham Park

Retaining Authenticity

Technological advancements of this period led to them becoming more economical to produce and heat and consequently led to a heyday for large-scale manufacturers such as John Weeks & Co of London and Mackenzie & Moncur of Scotland. And as we know, Richardsons of Darlington installed glasshouses at nearby Attingham Park around this same period, with much of the ironwork we have refurbished and reinstated from these buildings having survived, (view that project here), along with documents relating to their purchase and drawings. So, we do know fairly accurately what this glasshouse would have looked like.

We are using our Victorian specification to replicate the 1900’s glasshouse, which is the perfect platform to reproduce these grand old structures accurately. The National Trust said:

“The general aesthetic will be consistent and recognisable to visitors of National Trust properties and their glasshouses but with the intricacies of Benthall Hall intertwined. The existing character will be maintained, ensuring the changes are sympathetic to the overall historic context, character and appearance. [Whilst White Cottage’s unique] combination of materials will ensure the longevity of the glasshouse and will help with lifecycle maintenance of the elements usually difficult to access.”

Our Victorian greenhouses share the same portal framed structure of their forebears but benefit from advancements in materials making them much easier to maintain

The Cold Frames

A key part of the reinstatement will be the cold frames which extend the full 12m along the side of the south-facing greenhouse and, as mentioned earlier, are unusually wide.

Most often used as a protective stepping stone to harden tender young plants off before planting out in the main garden, or as a buffer zone for less hardy plants during the coldest months, being able to reach inside with trays of seedlings and having some height for larger plants are two typical and desirable features of a cold frame design. But at Benthall they will be used to showcase some of the alpine species Maw also collected and nurtured almost 150 years ago. The wide but shallow proportions of the cold frames are the perfect stage for the stunning display of traditional terracotta alpine pans Nick and his team fill with these delicate and characterful plants from Benthall’s collection.

The new cold frames benefit from gas struts which make lifting the large lids much easier than it was 100 years ago. It’s the perfect stage for Benthall’s alpine collection

The new cold frames will also benefit from a recent development of ours. An idea languishing on the drawing board for some time, as these things tend to, we were spurred into action by the demands of this special cold frame, acknowledging that our frustrations with our own incumbent design would only be exacerbated on this larger scale and taking notes from Nick on how cumbersome the old frames were, it was time to fast track some design innovations of our own. Combining a painted Accoya framework with much lighter and maintenance free coated aluminium lids (as our greenhouses do) and with the discreet addition of gas struts, they remain in keeping with the greenhouse whilst making the huge lids much easier to operate than they were 100 years ago.

Inside the Greenhouse

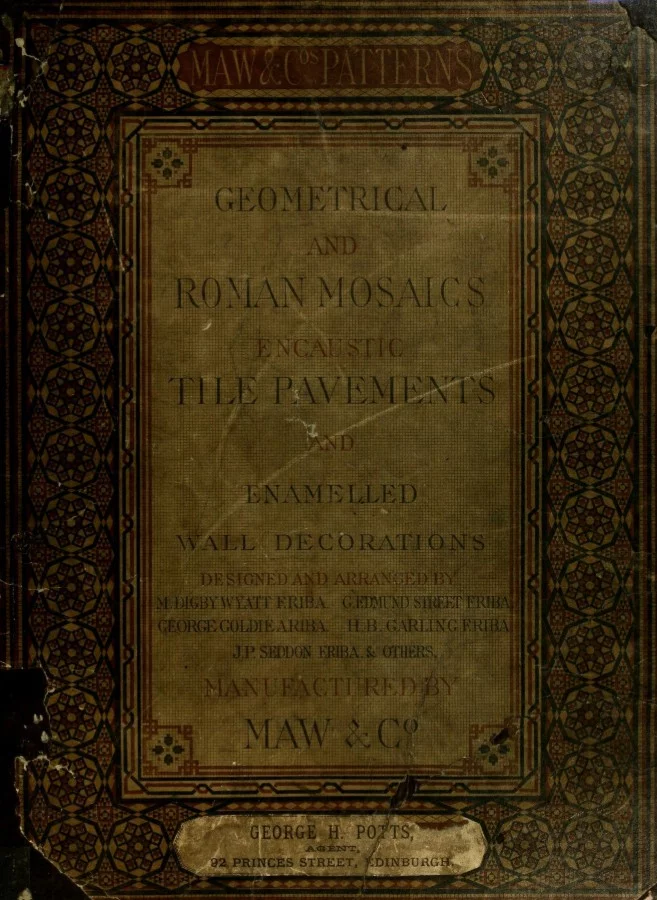

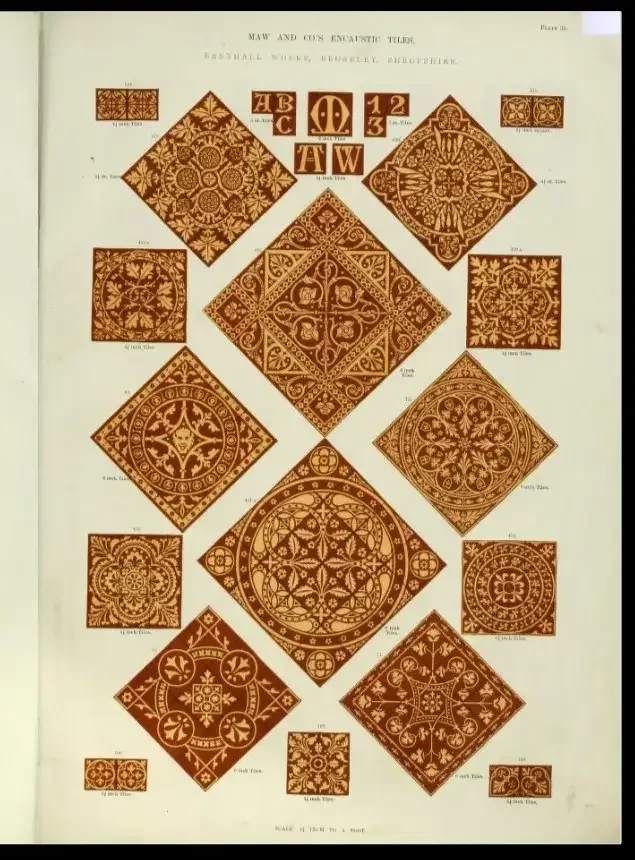

Inside, the layout replicates what the National Trust’s archaeology report tells us was there before. A central partition will divide the growing space into 2 zones where different growing conditions can be maintained. One partition will be dedicated to the seasonal staging of Benthall’s inherited plant collection and the other available as a more multifunctional space. Some original Maw & Co tiles have been returned to the estate and have been set into the floor.

Left, Original Maw & Co tiles decorate the internal floor of the new glasshouse. Centre and right, an original Maw & Co pattern brochure presents similar designs

“The proposal to reinstate the glasshouse at Benthall Hall in the Old Walled Kitchen Garden will enhance the historic environment by offering a structure reminiscent of Benthall’s rich history and reputation for gardening. The gardening staff will be able to grow plants that require protection from the cold weather and can be enjoyed by the visitors.

This will allow visitors, members, staff and volunteers to further appreciate the works of previous inhabitants and the present staff at the property in the art of botany and gardening.” National Trust Design and Access Statement, 2024

The new glasshouse is lovingly cleaned on a weekly basis

More than a century has passed since the last of Maw’s crocus bloomed in its original bed, but the reinstatement of the glasshouse is an important milestone in the journey Benthall Hall’s team are on to restart the work he began. This includes recreating the collection of Croci he describes in his monograph (including Crocus danfordiae – one of the species Maw named and one of the smallest flowered alpines, with delicate 1 to 1.5cm blooms which can easily be lost in a garden but work perfectly in pots in a glasshouse where their fragile beauty can be both admired and protected), and reintroducing other alpine plants described as being in the garden by William Robinson in his visit in 1881.

It has been a privilege to recreate this beautiful, Victorian glasshouse which was so integral to the garden of Benthall Hall’s long history of botany, cultivation and taxonomy. We’re passionate about making greenhouses that are truly synonymous with the Victorian and Edwardian eras; periods which marked a golden age of greenhouse design and where the efficacy of growing under glass was combined with aesthetic elegance and innovative engineering.

The new Benthall Hall Victorian greenhouse is now open to the public allowing visitors to experience how George Maw was using his glasshouses, over 150 years ago. More information on visiting this National Trust property is available here.

Credits

1) http://www.mawscraftcentre.co.uk/history.php

Maw & Co Tile Catalogue https://archive.org/details/patternsofmawcos00mawc/page/20/mode/2up?view=theater

3) The V&A – Arts and Crafts, an introduction. Accessed here: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/arts-and-crafts-an-introduction?srsltid=AfmBOopmX6MX6TQYmjMpH7vuxwAx77bVdctgcNf3_3flhp1n6lFY-CdK

4) William Robinson Gravetye Charity. https://william-robinson.org.uk/william-robinson/

https://www.greatbritishgardens.co.uk/william-robinson.html

5) Biddulph Old Hall. https://www.biddulpholdhall.co.uk/grounds-gardens/

And special thanks to Nick Swankie, Gardener in Charge, Benthall Hall for sharing his wealth of knowledge and passion for the gardens, his deep appreciation of what we do and his unwavering supply of tea and cake.

Comments

This article doesn't have any comments yet.